Women Rule the Ivies

Higher education’s most well-known and selective institutions will be mostly led by women this year.

Six of the Ivy League’s eight private research universities are slated to have female presidents this fall: Harvard University, Brown University, Columbia University, Cornell University, University of Pennsylvania and Dartmouth College. It’s the first time the group of elite colleges will have women at the helm of six of eight campuses, nearly 30 years after Judith Rodin became the first woman to lead an Ivy League school in 1994.

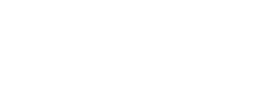

It’s a year of firsts for the Ivy League: Claudine Gay, the dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, will be Harvard University’s first Black leader. Nemat “Minouche” Shafik, president of the London School of Economics, will be Columbia University’s first female president. Sian Leah Beilock, president of Barnard College, was tapped to be the first woman to lead Dartmouth College in its more than 250-year history.

Beilock, Gay and Shafik are stepping into their roles during a pivotal time for women and students of color in higher education. Colleges across the country have been navigating how best to support students following the Supreme Court’s dismantling of abortion rights last summer. And Gay will be leading Harvard this summer after the Supreme Court decides the fate of using race in college admissions in a case where Harvard is a defendant.

Beilock is also taking the helm following Dartmouth’s 50th anniversary of allowing women to attend the college. (Though founded in 1769, Dartmouth only began admitting women in 1972; Columbia was the last Ivy to admit women, opening its doors to them in 1983.)

“I imagine a lot of people will ask me what it means to be Dartmouth’s first female president, and for some, they might think that I should not talk about that, I should just talk about being a president,” Beilock said in a video statement to Dartmouth’s community. “But my research as a psychologist, and my colleagues have really shown that having multiple identities — I am a researcher, I am a president, I am a teacher, I’m a mother — all of those things actually impact what we bring to the table.”

But don’t let the prominence of women leaders in the Ivy League mask the reality of college leadership across the country. The gender power gap in higher education persists.

Rodin, who was president of Penn from 1994 to 2004, led her campus when women and minorities leading colleges was a scarcity — about 12 percent of the presidents at 3,200 colleges were women at the time.

Women have outnumbered men on college campuses since the 1970s, according to a report from the Women’s Power Gap Initiative, created by the Eos Foundation in 2018, and the American Association of University Women.

Yet, women made up only 22 percent of presidents leading the top 130 research institutions in 2022. Women of color were nearly absent in those top roles at about 5 percent.

“Women of color represent the fastest growing segment of the college population in the United States,” researchers said. “Yet, scan the faces of those who wield power at our most prestigious universities, and you’re still likely to see the all-too familiar image of another white man.”

The higher education power gap is not a “pipeline” issue, as many like to put it. Women have received the majority of PhDs, a preferred qualification to lead a college, for more than a decade, and nearly 40 percent of all academic deans and provosts are women — positions from which about 75 percent of all presidents are drawn.

Beilock was once an assistant professor, decades before being tapped to lead Dartmouth. In an interview with Women Rule, Beilock said it’s promising to see academics taking on top leadership roles at universities because understanding what it means to be a faculty member, to teach students and to interact with staff, is a key part of leading at university. (Women Rule also reached out to Gay and Shafik, but their university spokespeople said they won’t be available until they start their roles in July.)

When asked if she’ll ever tire of being asked why it’s important to be the first woman to lead Dartmouth, Beilock said: “No, I like it — it’s important to show that different people can take on leadership roles at any institution.”